Book Review — A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement

A late bloomer becomes an animal welfare legend

There was a lot of low hanging fruit to pick for an animal rights advocate in late 1860’s urban America. Cruelties were everywhere you looked. To name just a few:

1500 horses per month broke their legs and were summarily shot after slipping on the streets of New York City.

Pigeons were deliberately mangled before shooting contests so they’d fly more crooked and be more challenging to hit.

Bad tempered zoo elephants were beaten for hours until they finally submitted (“It’s the only way to do,” the trainer explained. “Mild punishment only aggravates an elephant.”)

Animals were operated on while alive, with no anesthesia.

Stray dogs were strung up and beaten to death with rods as a form of animal control.

Slaughterhouses were barbaric scenes of slashing and bashing and squealing — all taken in by local children, watching and jeering from the sidewalk.

Not everyone applauded what they saw, but no authority figure was stepping up to make animal rights their main cause. That all changed when a washed up 53 year old diplomat named Henry Bergh stepped onto the scene. In 1866, after a couple decades of galavanting around Europe trying to be an artist, Bergh returned to New York and founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA). He became so influential that other animal defenders started referring to themselves as Berghists.

A Traitor to His Species tells Bergh’s tale. The book is written by Ernest Freeberg, who has the perfect name for someone doing his best to free Bergh’s story from the shackles of obscurity.

The book gives a broad overview of the animal advocacy movement in late 1800’s America. It’s an easy, fun read. Even if you don’t really care about the origin of the animal rights movement, you’d probably like it just for the oddball characters and fascinating anecdotes. There’s Kit Burns, the dog fighting king of New York, who staged spectacles where audience members would enter the ring and bite the heads off of live rats. There's the person who gave his entire fortune to the ASPCA because he “was haunted by a premonition that he would soon be reincarnated as a carriage horse”. And there’s Bergh in the thick of it all, demanding PT Barnum stop feeding live rabbits to snakes one day and telling slaughterhouse owners that their soul’s would be eternally tortured the next.

The book is also an inspiring story about a late bloomer finally finding a way to use his immense privilege to do some good in the world.

I think there is a lot to be gleaned from analyzing Bergh’s life arc. You’re probably not fabulously wealthy or politically connected enough to have the president give you a diplomatic post despite your general uselessness. But I bet you are already quite rich by the standards of total world income, given that a $40k annual salary in the US means you are in the richest 3% of the global population.

And maybe, like me, you have this sense that you’re full of untapped potential. You probably feel you could be doing more good in the world, but you’re held back by inertia and excuses and fear. With each passing year it’s easier to tell yourself that you’re too old to do X or Y.

All excuses for inaction feel flimsy when you read about old-ass Henry Bergh starting a successful company, enacting tons of anti-cruelty laws, and fearlessly brawling with abusers all over New York City like an animal loving Batman.

Bergh finds his calling

Bergh not a previously successful person who decided to take another swing late in life. He had been a total flop.

Born into a wealthy family, he could afford to spend the majority of his adult life hanging out in Europe trying to be an artist. His dream was to be a playwright, but he was so bad that a theater manager who read some of his work said, “There was positively no merit, and I wondered at his persistence.”

A new and more suitable avenue to apply his innate doggedness presented itself after he got stationed in St. Petersburg as a diplomat. He became upset with how Russian carriage drivers treated their horses. One day, in a scene that could have been pulled straight from a Dostoyevsky novel, he witnessed a peasant savagely whipping a horse. He felt compelled to act to help the animal. He stopped his carriage, summoned all the diplomatic authority he could muster, and commanded the abuser to stop. To his delight, the man listened to him, tossing away his whip.

That thrilling success was enough to make him move home to New York and spend the final 25 years of his life fighting for animals. While he didn’t accomplish all his goals, there’s no doubt he was happier. A year after starting the ASPCA, he told a friend:

“I have sought pleasure — or perhaps I should say happiness, in every quarter of the world. And I assert most unqualifiedly, that one day employed as each one of my days is now — in defending the dumb servants of mankind from their cruel oppressors, yields me at night a sum of supreme joy not comprised in a month of former days.”

The advice to find your passion and follow it is kind of passé these days. But reading a quote like that makes me think we should all be trying harder to find a vocation we truly love.

A man on a mission

While Berg might have been an inconsequential old man who had accomplished exactly nothing for his first 53 years, he was still a rich guy with powerful friends. Rich people with a purpose in 1860’s NYC could apparently get things done very quickly. Not too long after his St. Petersburg conversion to the cause, Bergh founded the ASPCA. He then convinced the New York state legislature to pass an animal welfare law that vowed to protect “any living creature” from cruelty.

Most importantly, he somehow got language into the law that allowed ASPCA agents to make arrests if they saw an animal being mistreated. There were previous anti cruelty laws on the books, but they didn’t have real teeth behind them. Empowering agents to enforce the law was a game changer for the animal movement.

Bergh was riding high at this point. The early legislative success might have made him a little too bullish on how easy it would be to get the masses on his side. When announcing the founding of the ASPCA, he presented a manifesto:

“The blood red hand of cruelty shall no longer torture dumb beasts with impunity,” he announced. The cause was mercy, “a matter purely of conscience” that should unite all men and women of goodwill [...] Berg proclaimed that this was “a moral question” that had “no perplexing side issues.”

As if he wanted to immediately prove himself wrong on the “no perplexing side issues” part, he started off his new career by going to war on behalf of not cats or dogs or horses, but the lowly turtle.

A master of publicity tries to expand the moral circle

Bergh was canny. To build buzz for the ASPCA, he deliberately sought out a legal case that would get good press coverage. He found one when he noticed how turtles were being treated like unfeeling cargo while being imported from Florida by boat. The turtles were laid on their backs and tied together by ropes that pierced their fins. This was enough for Bergh to proclaim the turtle importers were violating the state’s cruelty laws. He had a ship operator arrested.

Bergh was mostly mocked by the press for being crazy enough to care about the welfare of turtles. He didn’t mind. He realized that it was important to get any press at all if he wanted the movement to gain momentum.

His plan worked brilliantly. He quickly became a staple in the papers. He was mostly hated by the editors and commentators, but he picked up supporters too.

While he knew the controversies were helping his cause, he was not the type to do a flashy arrest and then dash off to do his next provocative deed. For the first few years of his time at the ASPCA he acted as his own lawyer. Though he never finished college and had no legal training, he had, in his own words, “zeal and common sense” and that’s all that was required. He did quite well at his trials, which probably added insult to injury for the real lawyers who had to spar with him.

He lost the turtle case, but he considered it a win for the rest of his life because it gave him the chance to get his views out in front of millions of readers who followed along in the press. It’s worth pointing out again just how unusual Bergh’s views were. The country was not that far removed from treating a whole class of humans as property, yet here was a guy saying even reptiles deserved our respect. I wish the book had spent more time investigating how Bergh came to have such a wide circle of compassion when it came to animals. All we get is the sense that it sprung from religious motives:

“The new anticruelty law staked a radical claim that animals enjoy the right to be protected from avoidable pain and suffering. But even if humans accepted this idea in principle, did that duty extend to all creatures? Just how far down the chain of being did this protection against cruelty go? Bergh thought all the way down. When the “Great Creator” gave life to “the poor despised turtle,” He also gave it “feeling and certain rights as well as ourselves.”

Bergh spent his life walking that walk. He went to bat for rabbits, rats, and other less loved animals.

I like to imagine that if Bergh had lived to see it he would have applauded the cutting edge work being done to look into the suffering of long neglected classes of animals, like those in the wild, or insects.

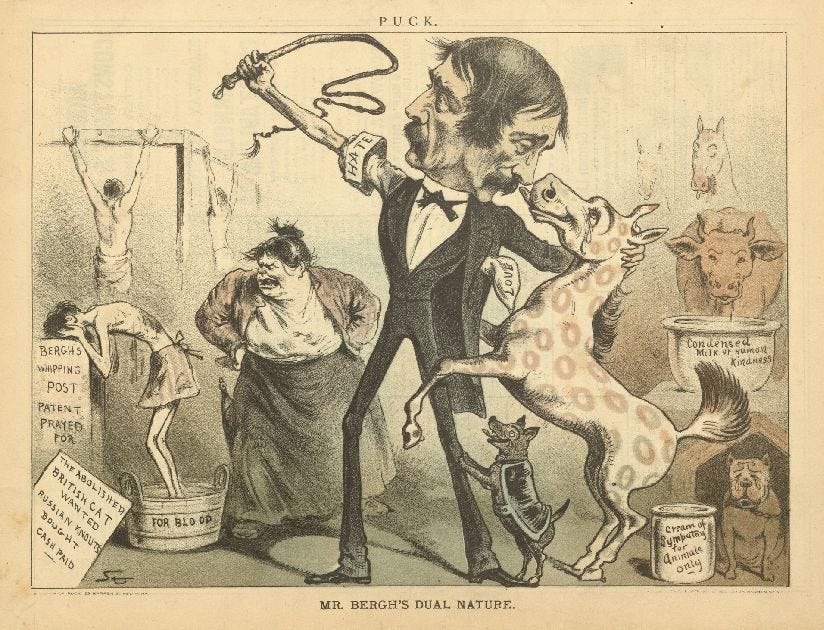

Animals get love, humans get pounded

Ironically, this sensitive and caring guy was absolutely convinced that the best way to change human behavior was via corporal punishment. He begged his powerful friends to enact a law that would let him publicly flog animal abusers. He suggested the construction of whipping posts around the city and offered up room in the ASPA offices for spankings. He fought for this outcome hard. Everyone told him it was insane and he finally backed down.

That didn’t stop him from doing the next best thing, which was going around NYC in a bellicose manner, confronting anyone he determined to be breaking an anti-cruelty law. He mostly got into verbal spats, but he was known to grab people by the collars and pull them out of their carriages if need be. As is usually the case in small startups, the top deputies took on the same traits as the boss. Soon, there were all kinds of ASPCA agents aggressively engaging with animal abusers. It’s not surprising to learn that some of these people were severely hurt or killed doing their job, though Bergh somehow escaped injury every time.

Even as some of his peers started to have success with a gentler approach, Bergh stayed fierce til the end. He was utterly convinced that someone wicked enough to hurt innocent animals would only respond to force. Reflecting on his life, he felt that, “The only mistake he had made in this work was ever thinking that he could change the behavior of cruel men and women by showing them mercy and compassion.”

Horses had it rough

It’s hard for us moderns to appreciate just how bad life was for a horse in 1800’s America. Animals on modern factory farms are crammed into tiny spaces and can barely move. Old timey horses faced the extreme end of the opposite problem: unrelenting physical labor.

Every horse in the country was almost constantly pulling a heavy load of some sort or the other. They carried garbage, went into mines, transported building materials, and pulled streetcars. I didn’t know until reading this book that they pulled goods down the freaking Erie Canal. They’d go from Buffalo to Albany and back, trekking the 700 miles while towing 50 ton barges. They developed awful sores from the relentless pulling against their harnesses. Bergh called them the most “inhumanly and wickedly treated” of all horses. But the economy depended on those goods getting moved. As one advocate for the interests of the shipping industry bluntly put it, “the prosperity of the canals depends upon torturing horses.”

A typical horse employed by a streetcar company in New York City pulled giant carriages of people 18 miles a day before going home to a dank stall and receiving little food. If they didn’t move quickly enough they were hit in the head or stabbed in the side. In one case documented in the book, a horse that refused to get up was forced to do so after an actual fire was lit underneath its belly.

The horses met their end in gruesome ways. Some collapsed from exhaustion, starved to death, or got infections. Others suffered severe injuries, such as when their legs got caught in the tracks, or when they were savagely beaten by their owners.

The ones that survived a few years pulling streetcars eventually wore out, at which point they were sold at low prices to poor people. Then the cycle started all over as their new owners tried to wring another year of hard labor out of them. Only once the horses could literally do no more work were they left to die on the side of the road or sold to a rendering plant.

Bergh and others fought hard to make lives better for these lowly creatures. The main issue they seized on in the cities was that the horses were pulling cars with too many people on them. Much like today’s NYC subways, people crammed into the streetcars during busy times.

The crowding made the cars way too heavy for a horse to safely pull. When Bergh struggled to pass a law that would limit this overcrowding, he, of course, started taking matters into his own hands.

“Snowstorms proved especially traumatic for the trolley horses, as tracks clogged with snow and ice, pavement grew even slicker, and every pedestrian sought refuge in a streetcar. Like an avenging snow angel, Bergh would appear in the midst of these “blinding storms,” bundled but radiating a magnetic authority that “no man dared to gainsay.” ‘Back to the stable, sir,’ he would order the drivers, shutting down trolley lines when he found horses struggling to carry overloaded cars through the drifts.”

Bergh and other ASPCA workers started regularly stopping carriages that were carrying too many passengers or clearly using unhealthy animals. This caused legendary traffic jams and stoked fury amongst passengers. Yet these disruptions, coupled with vigorous campaigning against the large corporations that owned the streetcars, eventually bore fruit. Laws were put in place limiting the amount the horses had to pull.

There is still a subset of the world that’s obsessed with seeing how much weight horses can pull. Sad and strange as that is, at least now it’s a sideshow and not daily life.

Incremental wins are not always what they seem

There was one general class of animals that, in Bergh’s opinion, won the suffering olympics — the livestock who had the unfortunate luck to have been bred out of state and shipped into NYC.

This quote, not for the faint of heart, summarizes how Bergh came to hold that view:

“No regulations prevented shippers from using every possible inch of space, so they often packed steer, pigs, and sheep in the same cars. The large animals had no place to lie down, which left the smaller ones at the mercy of the massive, panicked bodies lurching above them. In their frenzy and rage, the steer flailed, goring each other and the hapless sheep and pigs at their feet; before long, many suffered bruises, bleeding wounds, and broken horns. As the cars jounced across the continent, the strong animals drove weaker ones to the floor in their frantic attempt to make room. Those left underfoot rarely lasted long, tramped and suffocated, ‘trodden to jelly’. Whenever the trains stopped, drovers would try to revive the fallen by prodding them with sharp spears, forcing them to rise. As one eyewitness testified, ‘It requires a desperate effort on the part of a steer already weak and on a wet and slippery floor to recover it's feet while two or three other steers are standing over it, but, as long as any considerable amount of vitality is left, the prod does not fail to bring the animal to its feet.”

While things have improved, this practice of animal transport is still awful 150+ years later. Animals are crammed into tight spaces and shipped around the world in unsanitary conditions, often causing starvation and even drowning. Every year in the US alone, “more than 50 million cows, sheeps, pigs and countless chickens and turkeys travel across state lines” and “transport represents one of the most stressful times of an animal’s life”.

Despite the horrors, it does appear that less animals are literally “trodden to jelly” in our current system as they were in Bergh’s time. Some countries are starting to ban the practice. There are certainly more voices advocating for the transported animals than there were in the late 1800’s. The arc of the moral universe is long but bends towards justice, as the saying goes.

Those small steps we have made are in large part due to the efforts of Bergh and his peers. They first passed legislation in New York saying that animals needed to be let out for food and water roughly once per day. Then, realizing that the problem could never be solved by just one state, the disparate ASPCA groups across the country united, and got congress to pass a similar law. Animals would now get the right to rest, eat, and drink for five hours of every 28 hours they journeyed.

This win proved to have unintended side effects that some claimed were worse than the original state of affairs. The problem was that the animals refused to get back in the train cars after being let out for their break.

This outcome seems kind of obvious in retrospect. The animals had just left a hot, gross, deadly, cabin of death. The pain and suffering inflicted to get the animals back in the train car after getting their reprieve was apparently quite terrible to behold.

I wonder what other incremental victories for animals have similar unintended consequences. What comes to mind for me is the popularity of organic, free range dairy. These types of farms give cows a better life in many ways, but an excellent recent essay by Annie Lowrey in the Atlantic showed how even the most pampered cows in the world still suffer tremendous hardships. One big problem on the spotlighted in the piece is that organic dairy cows cannot get treated with antibiotics, lest their milk no longer qualify as organic. Injured cows who need antibiotics to heal have been left to suffer through grisly injuries with nothing but Tylenol.

Pushing for incremental changes is still great, don’t get me wrong. Getting laying hens out of battery cages and into free range systems is a big welfare win. It just doesn't make it any less depressing to learn about how many free range egg systems are still quite awful.

Until large scale factory farming is banned (a surprisingly popular policy position supported by half of Americans!) we’ll just keep seeing cases where supposed wins are not quite what they seem.

For his part, Bergh wasted no time trying to get people to stop eating animals. He didn’t even advocate for vegetarianism and he ate steak from time to time. He poured his heart into anti-cruelty laws and improved slaughter methods instead. Given meat consumption around the world is still rising 135 years after his death, it’s hard to argue with his choices.

Battling Burns and Barnum

Bergh famously challenged two prominent men who made a living exploiting animals. One was the famous PT Barnum, the other was a lost-to-history Irish gambling kingpin named Kit Burns. The Barnum stuff is interesting, but everyone kind of knows the deal with circuses. The arguments Bergh made against them are similar to those leveled at circuses and zoos today. Bergh is part of the reason that there are no more ‘Happy Family’ exhibits, where predator and prey of all kinds were kept in the same giant enclosure as part of some bizarre bid to convince people that all the animals at the circus got along.

In contrast to the familiar stuff about circuses, the sections about Bergh’s various attempts to nail down the elusive and powerful Kit Burns make you feel like you’ve been transported back in time to a totally foreign world.

Burns was a former gang leader turned saloon operator and dog fight promoter. He reveled in being the dog fighting king of the city, setting up frequent dog-focused events that were horrifying in both their brutality and their popularity. It was not just dogs fighting each other. Ratting was popular as well, where a dog was let loose in an arena filled with rats. Whichever dog could kill the most rodents was the winner. One pup caught 100 in 7 minutes. Humans would get in on the rat killing fun too. One patron was known to take on a dozen rats at once, biting each of their heads off in turn. Burn’s son in law had a standing offer to bite the head off a rat at any time for a “modest price.”

Bergh was relentless in pursuing Burns. That’s how he found himself with a police officer on the roof of Burns’s establishment, waiting for the perfect time to send the officer rappelling down a rope and into the pit so he could arrest Burns in the act of staging a fight. This was necessary because at the time no judge would convict someone for dog fighting without having eyewitness testimony of the event itself.

Burns escaped that initial arrest without conviction due to the sketchy nature of how political power and influence worked in late 1800’s NYC. But the trial was costly and generated bad publicity for him, and it was ultimately the beginning of the end for dogfighting in New York. Bergh kept up the lawsuits until he was able to get dogfighting banned in the city, the stress of which was said to contribute to Burns death by heart attack.

One tidbit in the Bergh vs Burns saga I found interesting was how the judges were sympathetic to those who wanted to ban dog fighting while being openly contemptuous of those who cared about the rat fights. They described rats as not animals but vermin. To the judges, killing a rat was always a good thing.

The distinction between which animals are deserving of care and protection remains relevant today. Rats, as smart and good natured as they may be, are still firmly in the vermin camp. Same with wild hogs, the shooting of which in the American south is a national pastime at this point. And of course the biggest group on the ‘we don’t really care about them’ side of the ledger are the farm animals we raise by the billions, in excruciating conditions, for slaughter.

How did he do what he did?

It’s not totally clear how Bergh was able to get so much done, and I wish more of the book had focused on his tactics. But there are several things that stand out.

He worked very hard

Bergh traveled long distances to give talks basically whenever any animal rights group asked him to show up. Travel in 1860’s America was not very comfortable, so this took a big effort on his part. He toured the country with relentless energy, lawyering, politicking, grassroots advocating, writing op-eds, giving speeches, and physically putting himself in harms way to combat animal abuse. The totality of this sheer force of will and high-energy pursuit of the cause led to positive outcomes for animals.

Getting his own hands dirty was crucial to his success, which meant his methods were not always replicable in other places. As the movement started growing, there began a pattern where Bergh would travel somewhere, get people all fired up, and get them to pass a new anti-cruelty law. Who could be for cruelty, right? But without “aggressive organization at the local level”, the laws would often not get enforced. Bergh was willing to do that aggressive organization, a lot of others were not.

He kept the main thing the main thing

He didn’t get distracted by other causes. He didn’t use his newfound fame to open a vegetarian restaurant or attempt to write a book. All he did was pursue animal abusers to the ends of the earth (or at least the state boundaries of New York) while doing his best to change the law to help animals.

Bergh also realized early on that while he would always be in favor of punishing individual acts of cruelty, the real culprits were usually the giant corporations employing the abusers and profiting off the backs of the animals. He focused on institutional change over changing individual behavior.

He was a compelling public speaker, and apparently pretty funny

The face of a movement cannot just be a mechanical, robotic, fact-spewing, downer. Apparently that’s what many people expected Bergh to be, given his famously dour and stern face. But once on a podium, he surprised people by including “a good share of dry, caustic humor” along with a “satiric wit.” He liked to jest that if people thought useless pests ought to be destroyed, then “a consistent application of that principle would require society to get rid of its drunkards and gamblers too.”

People can only get so motivated by doom and gloom. Bergh’s ability to lighten up an inherently depressing topic won him many supporters.

He had (some) convictions that were ahead of the scientific knowledge of the day, and he trusted this intuition over the experts

(Warning: be very careful before trying this at home.)Bergh was positive that all animals have the capacity to feel pain, which is becoming closer and closer to scientific consensus today. Another example is how he was positively convinced that there was a way to get snakes to eat already dead creatures. A leading scientist of the age, Louis Aggasiz, personally told Bergh he was wrong about this, but Bergh persisted in his belief. He was never able to prove it in his lifetime, but history certainly vindicated him. I’m no snake expert, but it’s a fact that while they might prefer live prey, they will eat dead food. An entire snake food industry exists to back this up.

He framed issues around how they benefited human health, instead of only focusing on animal welfare

To take one example, he realized that consumers would care a lot more about how animals were transported if it meant that they’d get to feed healthier food to their family. Bergh took great pains to prove that sick animals were being put into the supply chain and sold in the market, which horrified consumers.

He also leaned strongly into the idea that brutalizing animals had a detrimental effect on the health of one's conscience, and on their very soul. He constantly harped on the idea that abusing an animal, or even watching the abuse, had a corrupting effect on a person’s psychology. I do not think he would have been surprised to learn that recent studies have shown animal cruelty is a “red flag” which predicts violence towards humans.

His desire to elevate both humans and animals culminated in him co-founding the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, the first organization in America dedicated to protecting children.

He was fearless

Bergh made a lot of people angry. When he started going after cockfighting, “he received death threats from those who vowed to ‘cut him down,’ and papers sympathetic to Bergh’s cause felt obliged to warn against his assassination.” These threats never slowed him down. If anything, they pushed him to do even more. He seemed to have that Michael Jordan quality where he liked to both win and stomp on the grave’s of those he defeated. After the death of Kit Burns, he boasted that, “It has pleased Heaven to remove from this world the notorious Kit Burns, a conspicuous enemy to the cause we advocate [...] I drove him out of New York and into his grave.” After successfully convicting a man who killed a cat for no reason, Bergh called the defendant an “utterly worthless character whom it was a public and personal benefit for the law to chastise.”

He got press

He didn’t always get good press, but Bergh kept himself in the news. He had a knack for knowing what people wanted to read about, and he made sure to put himself in the center of that action. When he started arresting people for killing cats and succeeded in sending one man to Blackwell Island prison, pundits lost their minds. He was called “a crazy fanatic” who “deserves to be sent to the same island or to a lunatic asylum until he has recovered his senses.”

He wrote scores of op-eds and open letters challenging his enemies, no matter how famous or well connected they were. Public spats with the likes of widely known figures like Barnum, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Robert Roosevely (Teddy’s Uncle) served to get people around the country talking about animal welfare causes. There’s something triumphant about how this failed artist got to express himself creatively in these forums, the highlight of which might have been his 1874 battle with the powerful owner of the New York Herald over the ethics of trap shooting. In the pages of the Herald, Bergh let it rip, writing a fictional story about a hunter and a talking bird, with the bird saying:

“You are about to immolate me on the blood-stained altar of inglorious rivalry. And what will you gain by the crashing of my delicate limbs and ruptured arteries that a senseless target would not afford you?”

He made hard choices and didn’t look back, even if people called him nuts

While he was prosecuting turtle importers, people were ardently trying to get him to help protect the city’s dog population instead. Burns made the shrewd calculation that it was a losing battle to fight against the fear of rabies and gain a lot of enemies. He only turned to working for the city’s dogs later in life.

His work for dogs mostly consisted of lowering the fees that dog catchers could make so as to stop corruption in the dog flesh trade, as well as designing a system that drowned dogs en masse in the east river using a giant crate and a crane. That’s not how I imagine most activists envision “doing good” but it’s the kind of dirty work it takes to keep a movement headed in the right direction.

Again, he was not the most popular guy. At one point, a bill to repeal the ASPCA’s mandate passed in the New York state house of representatives before being defeated by just two votes in the senate. His authority was always tenuous, but he sure made the most of it while he had it.

He embraced new technology

It’s hard to read the book and not come away thinking the ultimate best friend of the animals is technological advancement. Bergh battled to not have carriage horses used on slippery roads, but only the invention of asphalt put an end to the carnage of so many horses breaking their legs.

Bergh didn’t just sit idly by and wait for the inventors to come to the rescue. He succeeded in developing a sling to rescue horses and introduced an ambulance designed to carry sick horses. He pushed to get pigeon shooters to use clay disks instead of live birds and ran contests to solicit ideas for better rail transport cars.

He was keen to develop more humane slaughter methods and sought to get people excited about developing “narcotic chambers” that would make the animals instantly pass out. He failed, but not for lack of trying. At one point he even got a group of rabbis together to tour kosher slaughterhouses. Instead of being horrified, the rabbis concluded that “no system could be better than the Jewish” and the kosher killing method (cow hung upside down, leg often dislocated, throat slit to let blood run for 5 minutes) showed “utmost tenderness for the animal.” Faced with this response, Bergh could only shake his head and wonder “why the profession of a butcher should be less merciful than the profession of a surgeon.”

Bergh was very flawed

Let’s tone the hagiography down a bit. Bergh was by no means perfect. Besides the already mentioned obsession with flogging, he was very xenophobic, especially towards the Irish. He was anti-vaccine and pushed hard to get people to not take them. He wanted a full ban on all animal experimentation with no exceptions allowed. He was willing to throw away long established friendships over minor disagreements. He was sure that only a military dictatorship could put America on the path to prosperity. And there was probably some truth to the claim by Bergh haters that he was pathologically obsessed with getting press as a way to stroke his own ego.

As far as rich white men in the 1800’s go, he could have been a lot worse. But I don’t want to give the impression that all, or even most, aspects of his personality are to be applauded.

Bergh’s legacy lives on

Bergh is a shining example of how one person, properly motivated and agentic, can move mountains. He got an idea in his head and ran with it, not caring how old he was or how much ridicule he’d get along the way. His approach understandably inspired people while he was alive, and his ideals have reverberated through time. I was recently listening to a 2024 podcast with the founder of PETA, Ingrid Newkirk. This quote stuck out to me as being very much in the spirit of Bergh:

“We knew we had to capture the press. And I always said, we’re not in this to make friends. We’re not here to win a popularity contest. We’re here to fight for animal rights. Animals need all the help they can get. We’ve never minded making fools of ourselves. We’ve never minded being mocked. We know we’re right and we know animals are just like us, and we know we have to say whatever has to be said and done to stick up for them. And so, that has lost us a lot of people.”

Modern activists who take “direct action” by infiltrating factory farms to save animals (filming the whole thing so they can get their exploits in the news) are also carrying on Bergh’s legacy. For better or worse, exposing what goes on behind the closed doors of factory farms is the challenge of the modern advocate precisely because Bergh and others were so successful at stopping the horrors that were happening in plain sight.

Bergh liked to say that his very first turtle case was the catalyst that moved his fellow uncaring citizens out of their “death like lethargy” and opened their eyes to the suffering around them. Thanks in part to him, there is much less lethargy these days. Bergh’s in your face, unapologetic, shoot first and ask questions later style is here to stay. He was a trailblazer in the truest sense of the term, and there’s no better place to learn about all his exploits than in A Traitor to His Species.