Recently, there was a big scandal in a city I used to live in. The city’s HR Director was found to be sexually abusing children. As the case unfolded, it came out that one of the other players involved was also sexually abusing a dog.

The whole thing is horrifying, but I was less surprised by the child abuse part than the dog stuff. I’d just never heard of something like that. I would not have been shocked if I’d already read Run, Spot, Run, by Jessica Pierce.

The book is a deep dive into the ethics of keeping pets, and bestiality is just one of many disturbing topics she covers. She explores all angles of our obsession with pets and pushes the reader to consider whether they might be complicit in more suffering than they realize.

While Pierce is an academic, the book is not dry. She writes with a brash, ‘I don’t care if you think I’m crazy’ type moxie that I greatly enjoyed. This quote gives a feel for the pugilistic way in which she goes after certain practices that most people don’t even think to question:

“Would I like to see all euthanasia technicians throw down their syringes and needles and refuse to participate? Yes. Would I like all consumers of pet culture to feel moral discomfort about their participation in an industry that results in the genocide of millions of animals a year? Yes, because only when we break the silence and truly acknowledge what is happening will we feel compelled to roar out in rage against the killing.”

Agree or disagree, that passage rips!

Another thing that makes the book fun and unique is that it has a bit of a gonzo journalism vibe. Pierce takes a pet euthanasia training course, goes to an Animal Hospital Association convention to ask hard questions, and, in a step I am not sure I could stomach, makes an account at a website for people who do sex stuff with animals.

That’s not to say that everything lands. At one point she suggests that human voices can be “quite frightening” to geckos, snakes, mice and hermit crabs. I mean, snakes and hermit crabs don’t even have ears. Is the idea that the vibrations would frighten them? This is a rare case where she doesn’t cite a source. There are sections where she overreaches with her animal rights zeal, and I say that as someone who gets made fun of for trying to shoo flies out of my house instead of smashing them.

Pierce doesn’t go as far as one person she quotes in the book, who describes pet ownership as nothing more than “chattel slavery.” She admits that lots of pets have a good life, despite their limited freedoms. She points out how pets can improve people’s mental and physical health. Plus, she owns dogs and cats that she loves very much. Overall, she just wishes that more people empathized with the plight of pets, and dreams of a world where we extend more legal protections to them.

This review won’t touch on everything in the book. If you want a wider ranging discussion of pet keeping ethics, I highly recommend Kenny Torrella’s piece in Vox called, “The Case Against Pet Ownership.” He even interviews Jessica Pierce herself!

I will go through some of the stuff from the book that I found to be especially surprising, shocking, and sad.

Do all the pets need to die by lethal injection?

I naively thought that euthanasia was almost entirely reserved for old and sick animals. After all, it seems like all the shelters I come across these days are “no kill.”

Pierce takes a euthanasia training course, and one of the first things she learns is that “no kill is a myth.” The teacher goes on to say that she knows of shelters with 95% euthanasia rates. They essentially act as killing grounds for local breeders who can’t sell all their puppies.

Horrifying, but at least there’s a standardized and humane way of doing all that killing, right? Sort of. Another belief of mine that got blown up was that all lethal injections of animals are performed by veterinarians. In fact, some states have no regulations around who can euthanize an animal, while others require just a 4 or 8 hour training course.

We are not even sure how many animals die this way, as no one keeps track. All we know is that: “We can safely make one statement about the deaths of owned pets: The vast majority of cats and dogs die by euthanasia.”

The course Pierce takes covers how much sodium pentobarbital to use, how to mix the solution, and how to inject it into the heart. That’s it, really. It’s taken for granted that dogs languishing in shelters, or that have specific ailments or behavioral issues, are better off dead. With these animals, we apply the opposite logic we use for humans in tough situations. We applaud humans who endure misery in the hopes that things will get better. But for an animal, suffering is always worse than death.

Death means nothing to them, we say. Pierce points out that we don’t really know how animals think about dying. We learn new things about animal capacities all the time, so who the heck knows how much suffering they’d be willing to endure to avoid death. Maybe a daily, or even weekly, walk with a volunteer is enough for a dog to want to keep living. It’s honestly more activity than I see some dogs in my neighborhood get.

I am still all for the painless killing of old animals who are clearly in tons of pain. But I appreciated Pierce’s approach to this topic. It forced me to confront the huge amount of killing going on, of creatures of all ages and health statuses, and to consider whether we all should be so happy to go along with it.

I was left wanting to learn a little more about what she proposes we actually do here. If she’s anti-euthanasia, and the shelters are out of room, is the plan really to just let all the unwanted pets run wild in the streets? (I don’t hate it.) Do we designate some remote island as “misfit pets land” and let them free there?

I know she’d eventually want to reduce the killings by regulating the breeding industry, but we have to take action now. It would have been nice to hear more from her on what shape that could take. She gestures at countries that stigmatize euthanasia altogether as a model we can follow, but those are places without the tremendous overpopulation problem we have in America. Would they be so noble in the face of the avalanche of unwanted pets that we have?

Shelters full of misery

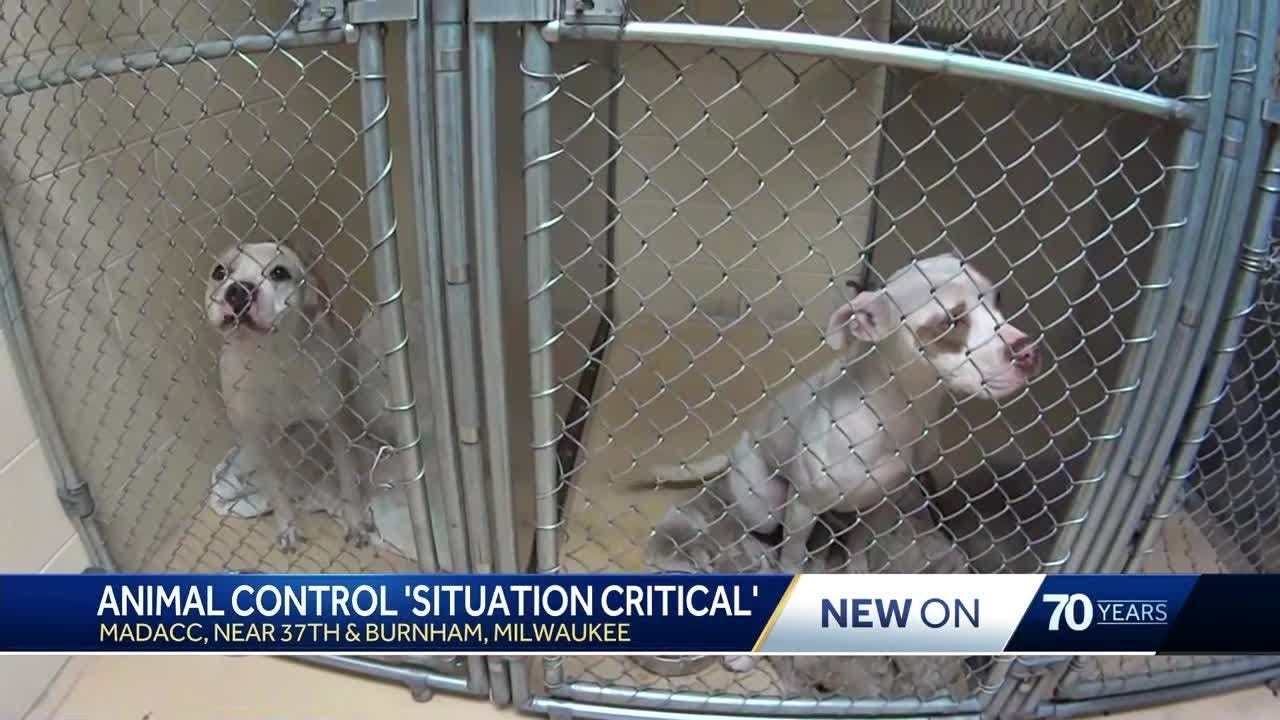

For Pierce, the worse part of our pet-keeping culture is the fact that so many animals live bad lives in shelters. Most people don’t think much about the plight of these creatures. They believe the shelter system is there to whisk any unwanted animal off to a new, loving family. Pierce vociferously disputes this notion.

This fantasy fuels the single biggest moral problem with our pet-keeping practices: millions of abandoned, unwanted, abused, relinquished animals languishing in our nation’s shelters, pounds, and humane societies. This is the cost, in real lives and real suffering, of our culture’s pet obsession.

6 to 8 million animals cycle through the shelter system each year, and Pierce estimates that at least half of those end up being killed. That’s a lot of death so that we can all keep buying French Bulldogs.

As good intentioned as most shelters are, they also shield animal breeders that flood the market with an unsustainable amount of pets from facing more backlash. Pierce believes that “shelters keep the pet industry from crashing in on itself since shelters control the surplus and thus keep the market for new product healthy.”

People who have worked in and around shelters refer to a “shelter industry.” Pierce notes how that term, industry, should set our spidey sense tingling.

There is no standardization across the country, no bar that all shelters have to clear. The Humane Society is just an advocacy group, not a shelter company that operates satellite locations. Anyone can start a shelter or a “rescue”. It’s sadly common for those places to get investigated and indicted on animal cruelty charges. A quick google search led me to a 2024 case against “The Devoted Barn” in Michigan, where, among other issues, 39 dogs were living in squalor.

There was also an uproar after substandard conditions were exposed at a shelter in Buffalo, NY.

Another issue with shelters is that they can facilitate long, unregulated, and deadly interstate transfers of dogs. A common pattern goes like this: A breeder in the south makes way too many dogs, knowing they can dump any that don’t get bought at the local shelter. That shelter contacts others around the country and finds one who has space and is happy to take in the eminently adoptable puppies. The puppies are trucked across the country, in sometimes appalling conditions. Once they get to their destination the cute young arrivals make it even harder to find takers for the older dogs already at the shelter.

The book discusses a case of breeder in Indiana who was caught transporting 62 (!) dogs in one minivan. He intended to take them from the breeding facility to a shelter out of state.

I don’t want to paint her too much as anti-shelter. The real villains of the story are the breeders, and her hope is that by regulating the sale of pets more we could clear out the shelters and make the ones we do have more humane.

Way more people are sexually abusing animals than you think

(Content warning: This is disturbing. But also, is it really that much worse than talking about what we do to the animals that we eat? Something to ponder.)

There’s a thriving subculture of people who engage in bestiality. They refer to themselves as “zoos,” based on the word zoophilia, the academic term for those who are attracted to animals.

It’s unclear how many there are. Pierce tries to consult the academic literature to learn more but can’t find much, determining that “maybe it is hard to get tenure if your research focus is bestiality.”

She takes matters into her own hands by signing up for an account on a bestiality enthusiast site BeastForum. At that time, before it got shut down, it had over a million members. I found the archived version and, whoa. That place was frighteningly active. The main forum topics had hundreds of thousands to millions of views each. I presume that is all happening on private messaging channels like Telegram now.

I’m grateful that Pierce poked around in there and that I didn’t have to. She quotes some haunting and vile stuff that I won’t repeat. She didn’t dare venture into the paywalled content.

The conundrum here is that, as implied by user names like “iluvmysheep”, many of the zoos feel they are in loving relationships with their animal and that no harm is being done. They talk about how to gain consent, without discussing whether that is ever really possible between a human and a sheep, dog, or chicken.

Perhaps my most surprising learning from this section of the book was that people have been doing this kind of thing for a really long time. The ancient Romans apparently had brothels where you could have sex with different animals of your choosing, with popular options being dogs, goats, and birds. Maybe we really are living in a simulation that’s actually a porno.

How can we make things better?

Pierce spends some time at the end of the book discussing what we can do to help all these struggling pets. She does not appear to have much faith that we can convince people to act better, and I don’t blame her.

She focuses on the the different structural changes we can make, mostly around laws we can change. She lists out 22 changes she’d make, such as limiting the sale of live sell animals, ramping up inspections of breeding and wholesale facilities, prohibiting “convenience euthanasia,” and giving more tax dollars to shelters and cruelty investigators. She also calls for “state appointed lawyers to represent animals in court,” which I think would be pretty darn cool.

Pet Keeping is Complicated

I have an annoying habit of walking around my city and making comments to my wife about what I consider to be bad behavior by pet owners. I’m constantly like, “Poor puppy/kitty, they probably don’t get walked enough/never get off that chain/don’t get played with/got declawed/never leave the side yard/eat an unhealthy diet/get yelled at too much. I wish I could rescue them.”

Run, Spot, Run was a satisfying read because it made my snobbishness feel somewhat validated. I take my dogs for 3 walks a day and pride myself in taking excellent care of them. Still, the book forced me to re-evaluate some of my own behaviors.

Is it mean to feed my dogs the same exact thing every day? Did I crate train them in an unhealthy way? Am I a moral monster for buying my dogs from a breeder even if I was unaware of all the problems with doing so at the time? Wait, am I actually one of the people that Pierce thinks would be better off with a pet rock?!

Overall, I think I’m doing okay. Especially when considering some of the other grim facts about pet-keeping I didn’t even cover. Here are just a few more not good things going on:

Pet abuse in general is rampant — The Humane Society estimates that there are hundreds of thousands of cruelty cases every year, which Pierce considers “a conservative estimate”

Lots of dogs bite people — there are about 4.5 million dog bites in the US each year, mostly due to irresponsible owners

Animal hoarding is all too common — “there are at least 5,000 cases every year, with up to a quarter of a million animals subjected to this kind of abuse”

Reptiles and fish make terrible pets and are probably miserable — 75% of reptiles don’t live past their first year as a pet. These animals have not been domesticated, are kept in too small cages, and get no stimulation.

Yes, more pets than ever in history are pampered beyond belief and treated like core family members. (I know mine are!) Yes, many of these creatures would not even exist if we didn’t want them as pets, and maybe a brief yet brutal life is better than none at all. But no, not all is good in pet keeping land just because there’s a thriving market for high end groomers, pet insurance, and animal probiotics. I don’t know of a better book for grappling with all these issues in a nuanced way than Run, Spot, Run.