Book review: The Monkey Wars

Exploring the pros and cons of using monkeys in medical research

Right after going vegan, I became convinced that all animal research, and especially primate research, was cruel and pointless. I read that animal testing has a 95% failure rate for predicting what pharmaceuticals will work in humans. I looked at a lot of terrible pictures of monkeys in labs. I listened to some podcasts with convincing anti-research guests. That was all I needed to put research in the evil category and move on.

I think it’s good to periodically question my assumptions, so I sought out a book that looked at both sides of the primate research issue. The best I could find was The Monkey Wars, by Deborah Blum. She spent a lot of time in early nineties talking to the top primate researchers, the cofounders of PETA, and everyone in between. Her series of articles on the topic won a Pulitzer, and she turned those pieces into the The Monkey Wars.

It’s a great overview of the history of our use of animals in experiments, the burgeoning understanding of monkey intelligence, and reasons for both caution and optimism when it comes to lab research on animals. It blew up my notion that humankind hasn’t benefitted much from primate research, but it also confirmed that the way we treat lab animals needs a massive overhaul.

It’s a complicated world

Try as she might to stay neutral, Blum’s sympathies clearly lie with the animal experimenters. She is charitable toward researchers doing even the most frivolous experiments. A guy who forces monkeys to interact with live snakes is not wasting taxpayer money, he’s actually built “a compelling case for the powerful connection between emotions and physical well-being.” When discussing a USDA inspection of a monkey research lab, she notes that one of the violations was “a monkey was crammed into a cage too small for him.” She calls that one of several “minor complaints”.

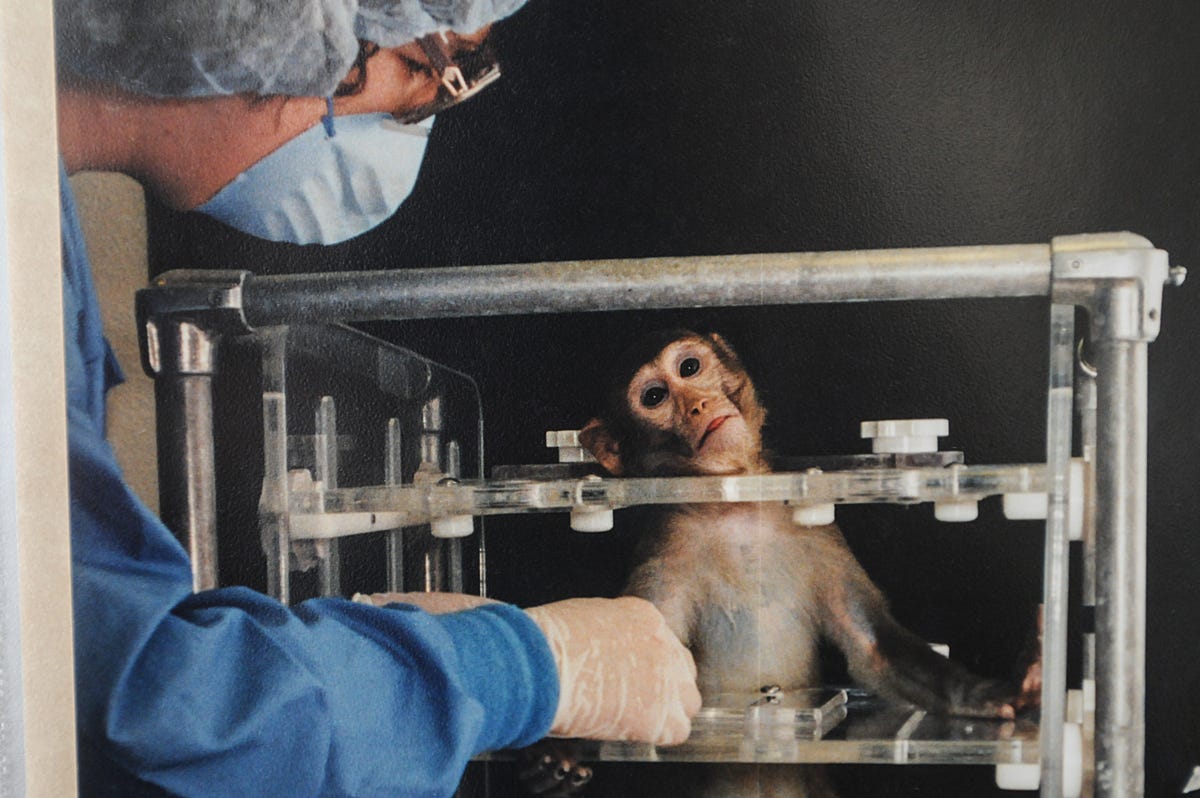

She also includes a bunch of pictures, but only of healthy and happy monkeys.

Still, she does an admirable job of giving ink to both sides and letting the reader come to their own conclusions. The question of what constitutes ethical research is a lot more nuanced than I realized. Where you stand on this issue comes down to what you consider to be a necessary evil, how much of a speciesist you are, and how much you think it matters that we do not torture creatures that are really smart.

I went in assuming that monkey researchers are heartless butchers sucking at the teat of the NIH without ever producing science that improves human health. After reading, I still think that is pretty much the case when it comes to those doing psychology studies. It’s a different story when it comes to combatting horrendous infectious diseases killing millions of people. I could never be the one purposely giving primates polio, but I can see why we did it.

To show how difficult it is to figure out where to draw the line, take the case of AIDS. Blum actually has a very negative view of how AIDS research in monkeys was progressing circa the book’s publication in 1994. She is pessimistic it will ever pan out, as are the animal rights activists, who fought hard to divert funding from monkey research into other prevention mechanisms. Then there was a research breakthrough in 1995 in large part due to primate studies. All of a sudden AIDS became a very manageable disease with the right medication.

It’s easy to say that we should only approve a limited amount of research that is likely to have a huge impact on human health. It’s harder to decide what constitutes a huge impact, and how much time we give people to figure out a solution. A lot of the researchers in the book struggle with this issue themselves.

Even Frans de Waal, considered one of the good guy monkey researchers by PETA, has a hard time figuring out where he lands.

“One chimp or one baboon for one human, I’m not sure that’s a good use of an animal. On the other hand, with something like AIDS, there are 40 million people infected. If you could stop that with the use of 1,000 chimpanzees, who am I to say we cannot? Sometimes, these are presented as very simple issues. And that is not honest.”

There’s a big part of me that still thinks it’s just flat out wrong to experiment on monkeys, and it would be better for our collective souls and the planet as a whole if we stopped altogether. It’s worth mentioning again that most research produces nothing of value. Oh, and sometimes we import monkeys infected with Ebola and narrowly avoid a massive pandemic. Ho hum.

Another part of me thinks about how the small sliver of animal research that does pan out can be profoundly beneficial. It might be better to look at animal research the way VC’s look at investments — the few winners are so successful they make the whole endeavor worth it. That’s fine in the abstract, but then I look at a picture of a mother with her child in a breeding facility, and I’m back to wanting to ban it all.

It’s just so hard. Because speaking of babies, my wife and I could not have one were it not for IVF, a technology that benefitted from experimentation on rhesus macaques. Would I really choose the reality where we never use monkeys in research and I also couldn’t have a kid? Maybe. I don’t know. It sucks. My hope is that advances in AI and synthetic biology can get us to a point where questions like that no longer have to be asked.

The arguments in favor of monkey research

The animal researchers have achieved some big successes. The granddaddy of them all is the vaccine for polio. For the vivisectionists, the polio cure acts as a protective shield with infinite hit points. It’s constantly invoked, even when the research in question could never remotely have that kind of impact. And they typically don’t mention the 2 to 5 million dead monkeys it took to produce the vaccine. Still, kudos to Jonah Salk and co.

There have been other benefits to human health, too. Blum:

In the 1950’s, primate researchers developed chlorpromazine, one of the most powerful drugs used to treat mental illnesses such as schizophrenia. In the 1960s, monkeys were used to develop a vaccine against rubella an din the surgical transplanting of corneas to restore vision. In the 1970s and 1980s, primate research helped track down tumor viruses, to improve chemotherapy. The now widely used vaccine for hepatitis B was developed largely in chimpanzees.”

That still didn’t feel that great to me. The book was surprisingly light on ways monkey research has tangibly benefitted human health. The pro-vivisection argument always seemed to cash out as, “Monekys are cool and all but they don’t have rights, so who cares what we do?” and “HeArD oF ThE PoLiO VaCcInE??”

So I went looking for important monkey research wins myself. Here are the best ones, in my opinion:

finding improved treatments for AIDS, ZIKA, Ebola, malaria, and rabies

developing better IVF protocols

improving organ transplantation success rates

That’s nothing to sneeze at! Plus, I’m probably missing stuff.

I’m not saying it’s a fair or just tradeoff given the tens of millions of monkeys sacrificed at the altar of those successes, and immense amount of suffering caused. I really don’t know. I’m just noting that humans have undoubtedly benefitted as a result of the experiments.

The arguments against monkey research

All monkey researchers seem to think they are on the cusp of going down in history as a great humanitarian. One guy says, “just like with Polio, I want the answers.” Unfortunately, that particular researcher spent his career proving beyond a shadow of a doubt that monkeys get lonely and miserable when you destroy their social life. Curing polio, he was not.

Here are some other experiments it feels like we could have pretty easily sorted into the “this isn’t going to have world changing impact” camp:

sewing baby monkeys eyes shut to test how that hinders their development

isolating baby monkeys with nothing but a spike riddled dummy to see if they’ll try to bond with it

shooting monkeys with a cannon to study blunt force trauma

using monkeys as live crash test dummies

shutting infant monkeys into “devices that would have trapped Houdini” and keeping them like that for months on end

proving monkeys produce more stress hormones when you put a snake next to their cage

Then there are the researchers who are open and unapologetic about doing research that won’t really move the needle for human health. After describing one guy’s experiment involving taking baby monkeys away from their mothers, Blum says “his latest work sheds little insight on human problems, he concedes, except by simple kinship.”

Activists are outraged not just because they experiments themselves seem pointless and cruel. They also see variations of the same experiments getting funded over and over. Blum summarizes why the animal activists were upset with a particular researcher, Seymour Levine:

“The federal government gives him millions; he keeps expanding his use of monkey separation; it seems like a never-ending cycle, more money, more monkeys yanked from their family, more money, more monkeys. How many times does he have to prove his point, that monkey feel safer in the company of friends or family?”

I’d take it a step further, and say that he really didn’t have to prove that point at all. But the money keeps flowing. It’s enough to make me think that maybe Alexey Guzey is right and we need to just ditch the NIH altogether.

Most of the researchers profiled in the book feel at least somewhat conflicted about what they are doing. Reading about the ones who are not, who almost seem to delight in being dismissive of animal rights, should make us all nervous.

Take researcher Stuart Zola-Morgan. He pioneered the field of scraping out pieces of monkey brains to see how it affected their recall. He also induced strokes on the operating table to see what parts of the monkey’s brains died. He admits to Blum that monkeys are highly intelligent, then says, “I hesitate to talk about how smart monkeys are because it tends to feed the animal rights movement.”

He never replaces a monkeys cheekbones after removing them for surgery. It would take too much time, plus he just kills them a couple years later to look at their brains anyway. But don’t worry, that doesn’t cause the monkey’s pain. (Zero evidence is presented to back up that claim.)

As if consciously playing up his role as animal advocate villain, Zola-Morgan makes it very clear that, “His own motivation doesn’t come from trying to find practical new treatments.” He is just insatiably curious, and hopes that others will use his research for good means. I’d rather the guy who is literally choking monkeys on the operating table to be motivated by something grander than scratching an intellectual itch.

His smugness jumps off the page. At one point, he unironically compares one of his findings to Watson and Crick discovering the double helix. He’s sure that his work is critically important, we just haven’t figured out how to apply it yet.

I have the advantage of reading this 30 years after the book was published. I looked into it, and we have nothing close to what he’s describing. In fact, at least according to Chat GPT, “Zola Morgan’s foundational research has not directly resulted in specific treatments for memory impairments in humans.” Ouch.

Blum is also particularly terrified at the idea of xenotransplantation. She spends a whole chapter worrying about what kind of diseases we could inadvertently spread by putting monkey parts into humans. There are all kinds of viruses lurking in monkey blood. Even the heralded Polio vaccine may have transferred some nasty compounds into unwitting recipients, because with the initial batch we hadn’t learned how to properly sterilize the vaccine. Kids of mothers who received the Salk polio vaccine got brain tumors at 13x the rate of those from unvaccinated mothers.

Overall, the animal activists say that the magnitude of suffering we inflict on monkeys trumps the benefits we’ve received, that lots of research is pointless and dangerous, that we’ve picked the low hanging fruit, and that it’s time to find new avenues forward for curing human diseases.

Extremists on both sides are annoying and cruel

I was so ready to glorify the heroic activists trying to stop the worst kinds of research. That partially happened, but only for certain people, like Christine Stevens, who show a little bit of open mindedness. Sometimes bitter hatred for any research gets in the way of an animal’s wellbeing.

The canonical example of this is what happened after PETAs first every undercover investigation, The Silver Spring case. It involved a group of monkeys who were having their spinal nerves severed to the induce limb paralysis. After being paralyzed, the monkeys were prodded and shocked in various ways to see if they could somehow use the paralyzed limb. It was grim, sadistic stuff. (If you were wondering, none of the monkeys ended up magically being able to heal their nerve damage.)

Not only were the experiments gnarly, the conditions were horrifying. It was a dank, roach-infested lab and the monkeys were kept in an appalling state of filth. PETA’s cofounder, Alex Pachecho, worked at the lab and then revealed horrific conditions to the press. This led to public outrage and criminal charges against the head of the lab.

When the story first broke, the advocates had all the goodwill. There was bipartisan support in congress to help the monkeys. They sent a letter to the NIH signed by 250 congresspeople arguing that the surviving monkeys from the lab should be sent to a sanctuary.1

But the top brass at the NIH was vindictive and petty and didn’t want to give the advocates a win, so they pulled a last minute switcheroo and sent the monkeys to a research facility in Tulane. This incident started an overall battening down of the hatches for the research community. Instead of looking at the horrified reaction of the public and changing their ways, they decided the public was too dumb and too sensitive to appreciate how real science is done. They also became world class dramatizers. Here’s Pete Gerone, the person in charge of the primate center in Tulane, talking about how he felt after a debate with PETA’s Alex Pachecho:

“I’ve spent 45 minutes looking into the face of evil. I’m not saying Pachecho is the devil or anything like that, but what was emanating was evil. And it’s changed how I look at the world. As far as God goes, I’m still agnostic. But I know there’s a devil.”

That quote is ridiculous. But if you look at what Pachecho did after the monkey’s went to Tulane, he doesn’t come across as a likable figure.

PETA secured a court order saying that the Tulane lab could not euthanize the monkeys. Their thinking was that the researchers would kill the animals to spite them, and maybe they were right. But what actually happened was that monkeys started getting super sick and the vets couldn’t legally euthanize them.

One particular monkey was declining in such tragic fashion that the researchers begged PETA to send their own vet to assess the situation. They did so, and the vet recommended euthanization. Pachecho didn’t care. He told Blum that he wouldn’t kill his own family member in a similar situation, so he wasn’t going to let them kill Billy the monkey. Pachecho was content to leave Billy, with his two paralyzed arms and his failing body, to shuffle around, wallowing in diarrhea, clearly miserable, to suffer until his very last moment. Thankfully a court of appeals sided with Tulane and approved the mercy killing.

There’s a lesson here, for everyone involved, about not letting personal biases get in the way of doing what’s right.

We need stricter rules on the research we allow

The researchers are (mostly) not monsters. Even the guy running an NIH monkey lab who openly pines for the good old days when he could run experiments on human prisoners (“The prisoners loved it. They got to lie around, eat candy bars”) tells Blum that he has his doubts about his profession:

“Once someone raises the philosophical question, once I really think about it, once I ask myself just exactly what is it that makes me feel I have a right to use animals, I’m at a loss for an answer. At the same time, my feelings are not so mixed that I hesitate to use animals for the benefit of mankind. I’ve never paused — it would be dishonest to say so.”

What could make him pause is an adjustment to the laws, just like we did with allowing research on prisoners. I’m no legal expert, but it seems like a good place to start is with regulating the psychological research.

Without guardrails, we get people like Harvard’s Margarat Livingstone. She is the one doing the studies where they sew a baby monkey’s eyes shut. Lately she’s also been doing the tried and true study of taking babies from moms and replacing the babies with stuffed animals. When asked by Harvard Magazine, in 2022, about the practical implications of giving captive monkey moms fake babies after stealing their real ones, she said, “I wouldn’t be surprised if touch and soft texture also play an important role in the bonding of human mothers with their babies.” I wouldn’t be surprised either! No one would be! So maybe wrenching even more babies from even more mothers is just no longer necessary and should be outlawed.

I think I could support a policy that says we use a very select amount of monkeys for absolutely vital research that has the potential to save X millions of human lives. Though when I really think about it, I’m honestly not sure I could. I empathize with the scientist who said:

“Even if I were absolutely sure that my particular research would improve the human condition, I would find it very difficult to attach a specific moral value to my findings that could persuade me completely that the ends justified the means.”

What I do feel confident about is that we should give the research monkeys a reprieve after a certain amount of time. After they do their service for humanity we should honor them by letting them live out their years in a sanctuary. Because as much as the research community wants to tell us that the monkeys like their climate controlled indoor environment, they want more space. You only have to look at how often they escape. Or read about how the chimps at a research facility in Washington State reacted when they first got access to a large outdoor enclosure.

It was such a different world, they thought it would frighten the animals. Instead, the apes seemed thrilled. […]

Deborah Fouts recalls that when the door opened and sunlight flooded into the room, Tatu first sat staring and then began screaming and hand-signing, “Hug, hug, hug,” before bolting through door. […]

They even opened the door on raining mornings. In the dropping rain, Moja sat grouchily within an outdoor structure. But Tatu climbed halfway up the cage, to a ledge, and just sat there, water running off her ears, dropping into her eyes. She signed quietly to herself, “Out, out, out.”

It would be so great to make that kind of moment happen for more monkeys.

Tough questions remain

The Monkey Wars took an issue I thought was simple and made me see it differently. Keeping monkeys in labs causes immense animal suffering, but it’s also contributed to more wins for human health than I thought. Wrenching animals out of the wild for research is bad on a number of levels, but some of the animals brought over were literally bought out of restaurant kitchens in Africa, minutes before the animal was to be killed and served. Research veterinarians administer poison and are easy to criticize, but without the vets who fought for change a lot more animals would still be living in isolated, barren cages.

All I can do is hope that we can ban the worst practices, donate to causes doing good in the world, and try to support the development of technology makes this whole question obsolete.

There were a lot of examples in the book of elected officials on the right and the left working to prevent animal suffering. It was heartwarming to read about, and further proof that animal rights is more of a bipartisan issue than most people think. Shoutout to Bob Dole!

if you are interested in a much more recent book on the same subject, may I suggest They All Had Eyes: Confession's of a Vivisectionist

It takes an Anti Animal testing stance, but Is written by a man who was formerly a professional researcher on macaques , It also talks touches on other species like rats/dogs/birds etc , and the ritualized animal abuse that serves as a hazing ritual into medical research academia